Polyphone Ecclesial Ministries in Post-secular Realities?

Ulla Schmidt, Aarhus University, Denmark

Over the past two to three decades, “polyphony” – or related terms like multi- or plurivocality – have been suggested as approaches to pastoral ministries such as preaching and pastoral care, congruent with theoretical and empirical features of contemporary western thought, cultures and societies. It is relevant to ask whether this term could also characterize ecclesial ministries more broadly, ministries that are part of, affected by as well as affecting secular and post-secular cultural, societal and political realities.

Polyphony has typically been justified in terms of one or more of three key points. One is postcolonialism, with its acknowledgement of long-lasting effects of colonialization in terms of hegemonic, discursive and epistemic powers working also “from within” subjects (Müller 2024; Kwok 2015). Furthermore, emphasizing how cultures are rarely “pure” and monolithic, but blended and intertwined, concepts and images of cultural purity are considered stereotyping powers which risk imprisoning imaginations of people and communities. To avoid exerting this kind of stereotyping powers, preaching ought to provide a kind of “third space” with a blend of cultural voices and perspectives.

Dialogical thought has provided a second justification. Empirical research has demonstrated how listening to and meaning in sermons is a dialogical enterprise (Ringgaard Lorensen 2013, Gaarden 2021). As argued by Russian literary theorist and author Mikhail Bakhtin, dialogue is essential to communication and understanding, and meaning emerges in the communicative interaction between dialogue partners (Rysstad 2019). It is therefore not in the individual mind, for instance the preacher on the pulpit, that meaning is authored, but in the continuous relationship between self and other. The addressees in the pews are not just listeners, but also co-authors, and this co-authorship is not only communicatively, but also epistemologically significant.

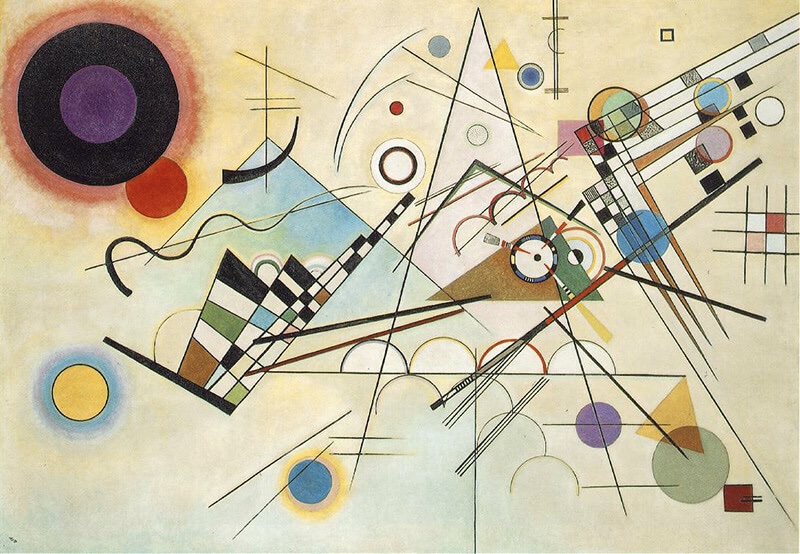

A third justification is rooted in reflections on the Trinity (Pembroke 2004), where “polyphony” is used to denote how oneness and difference form a unity in God, in terms of the relationality of the three (e.g. by David S. Cunningham 1998). In this context its musicological background is especially salient, referring to a multiplicity of tones and themes, each being necessary, but different components of a complete musical unity. It illustrates how oneness can be genuinely present when constituted by continuous self-differentiation.

“Polyphone” ecclesial ministries are participatory, in the sense that functions, people and groups have agency in performing ministries, rather than being passive consumers. Roles and authorities are shared and interchangeable. They do not belong statically to one position. They might shift, and with them the perspectives associated with roles and positions shift as well and interweave different localities and identities. This augments possibilities for dislodging or defamiliarizing ecclesial ministries from naturalized forms of knowledge, and opening spaces for imagining and creating new realities and ways of being.

Although lacking a precise reference, “post-secular” can justifiably be understood to point to features which warrant reflecting critically on the relevance of “polyphone ecclesial ministries.” Among those are complex tendencies of religious changes, rather than universal decline or growth; religion, including ecclesial practices, mutating in direction of plural, non-confessional, de-institutional, spiritual, experiential; less defined through binary categories, like sacred – secular, faith – reason. These features invite reflecting on ecclesial ministries as inclusive in terms of participatory agency, diverse in terms of expressions, and porous rather than distinct and delimited in terms of exchanges with contexts.