Vision, Leadership & van Gogh

Derek R. Nelson

Before he was a great-but-not-much-appreciated painter, Vincent van Gogh was a lousy-but-very-much-appreciated pastor. The details of this little-known chapter in his life are of some interest, I think, to those who are wondering about how early career pastors find sources of resilience to sustain them in their ministries, and also how pastors seeking to exercise leadership in their communities can do so effectively.

Van Gogh as a Pastor

Van Gogh’s father was a Dutch Reformed preacher, of the rather severe sort. Young Vincent had a good relationship with him, but was not close with his mother. He, and she, were haunted by the loss of another Vincent van Gogh, stillborn on the same date, March 30, as our painter friend would be born exactly one year later. Vincent often walked past the grave of the brother he never knew and saw his own birthday. It must have had an effect.

After some failings in love, work and art, van Gogh needed a new start. He hoped to become a preacher like his father. He was not considered a strong candidate by the theological faculty at Amsterdam because of his volatility and apparent mental instability. His refusal to learn Latin — he already was fluent in four “living” languages and did not wish to learn a dead one! — gave them the pretext they needed to deny him admission. Lacking a path to the usual credentials, Vincent volunteered to be a missionary preacher to the Borinage, a very impoverished mining region in Belgium. He went at the age of 25 and remained there two years.

His love for the people to whom he was sent could not be questioned. They didn’t think much of his preaching yet the called him “Christ of the coal mines” because of the way he tried to help impoverished people meet their immediate needs. He had only a pittance himself but gave almost all of that away to the poor. He gave all his clothing away except a single dirty outfit. The Reformed church that was sponsoring him provided rent for a room, which he gave to a single mom with several kids he thought needed it more. He couch-surfed for the last portion of his ministry until he was recalled to the Netherlands, on the grounds that his ministry was undignified and ineffective.

Interviewed years later, the pastor of a neighboring village recalled how Vincent sacrificed nearly everything to help the miners to whom he preached the gospel. “He preferred to go to the most unfortunate, the injured and the sick. He was prepared to make any sacrifice to ease their suffering.” And his compassion reached even beyond the human realm. The family with whom he stayed remembered “that if he saw a caterpillar on the ground in the garden, he would gather it up delicately and go place it on a tree”.

“As for his painting,” pastor Bonte continues in the interview, “I cannot speak as a connoisseur; in any event, it was not taken seriously. He used to squat on the slag heaps and make portraits of the women gathering coal there or leaving burdened with sacks.”

Then the pastor said something very provocative, though he meant it to diminish van Gogh’s art. In rendering his verdict he said, “We noticed that he did not reproduce things of splendor, to which we attribute beauty.”

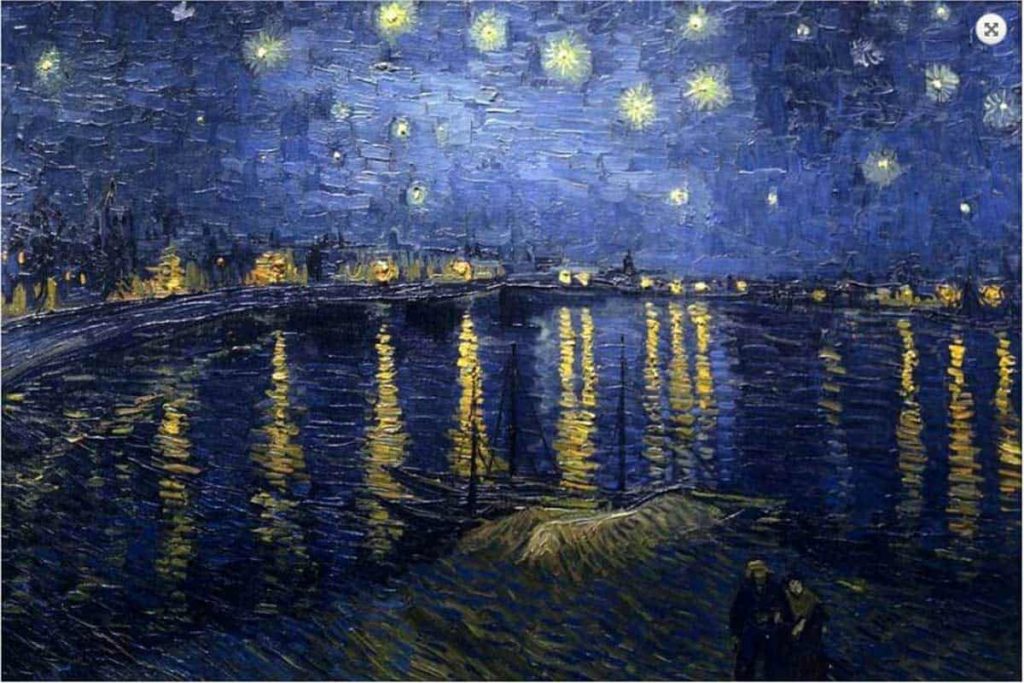

A later painting of some peasant’s shoes could be a prime example of this. It is frequently discussed by art historians and philosophers, and Martin Heidegger devoted several pages of his 1935 book The Origin of the Work of Art. Van Gogh was uniquely able to find beauty and wonder in simple things – a pair of shoes, a cleared cafe at night, a vase of sunflowers.

Two years later, writing his brother Theo, he conceded, “Now for more than five years, I have been more or less without employment, wandering here and there. I have lived as I could, as luck would have it, haphazardly. It is true that my financial affairs are in a sad state and that my needs are greater – infinitely greater – than my possessions. But I must continue on the path I have taken now. If I don’t do anything, if I don’t study, if I don’t go on seeking any longer, I am lost. To continue, to continue, that is what is necessary. With evangelists it is the same as with artists.”

The Pastor as van Gogh

Perhaps it is the same with evangelists and artists, especially a great one like van Gogh. I’m not an expert in art, certainly, so my view of what makes van Gogh’s painting so moving should be taken with a grain of salt. But there are two connections I see between his later artwork and the work of our programs at helping younger pastors turn the corner of competence to leadership.

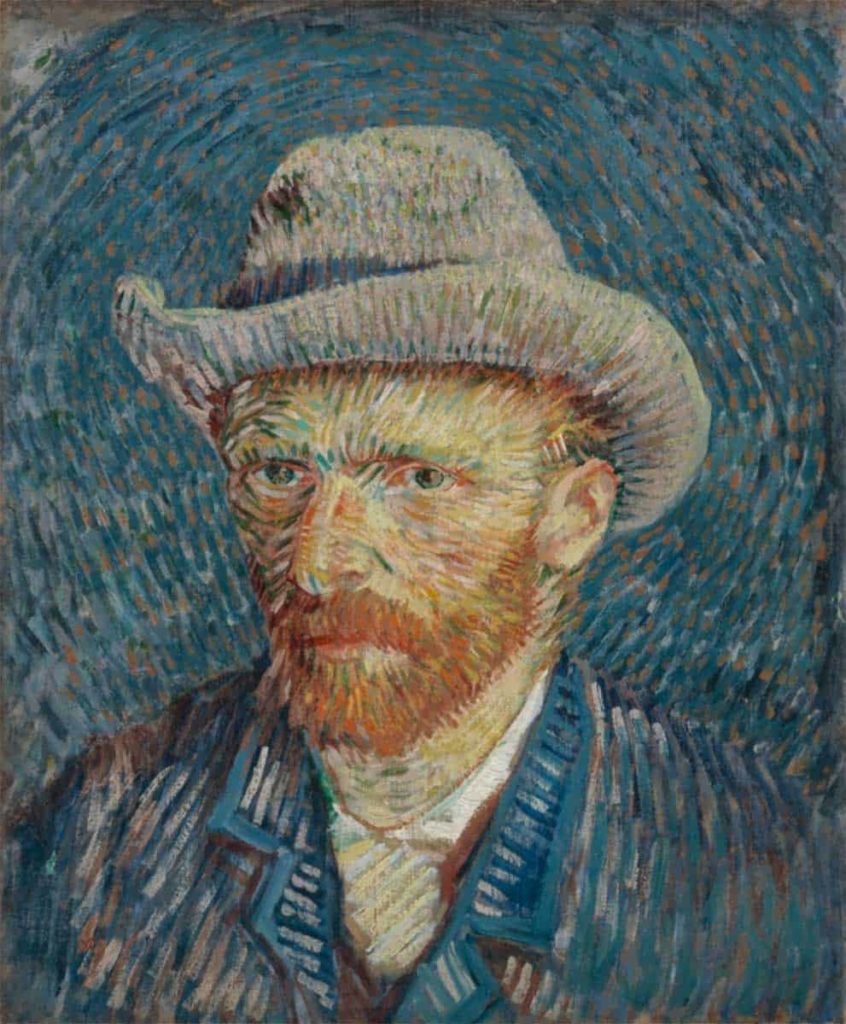

First is the way van Gogh is able to focus on the minimum number of included elements in his works. Rather than producing “realistic” portraits of what he is looking at, he sees more by painting less. The face has many features but it is the furrowed wrinkles that he emphasizes. His ultra-thick pigment builds up and up on the canvas, deepening the wrinkle and dramatizing the expression. The face is practically moving about, so much tumult and tension has van Gogh added. The background is more or less blank, the clothing substitutable, the rest of the body obscured. The radiating patterns of thick paint bring the viewer’s eyes to the center, which also defines the periphery as periphery.

It sounds like I’m saying the work is “simple,” but that isn’t what I mean. Rather, it is focused, and it focuses by omitting. Whatever would detract or simply would not add to the composition is left out. In a similar vein I was talking with a friend recently about a deceased former colleague who had a knack for assigning students just the right portions of a text. “Read pages 3-5, 41-42 and the bottom half of page 104” might be an instruction he gave. And there, in those few pages, was the kernel of the whole. In my early days of teaching I would worry about things like “rigor” and would thus probably assign all 150 pages of the book just to send a message that I meant business. Or I might worry, “I made them buy the whole book, so I’d better not assign just six pages of it.” But an experienced eye is able to name the periphery as such by keeping his or her own focus — and drawing the focus of those they lead — to the center.

Some pastors have, and all pastors who would be leaders need, this skill. There is so much to do that I mislead myself into thinking all must be done. And that all must be done by me. There is one thing that is needful, we read in Luke 10:42. Discerning what one needful thing is, is the stuff of experienced ministry. Community organizers talk about “slicing” or “cutting” an issue. Wicked problems are too complicated for any one intervention to solve, so leadership consists in helping to see where the cuts can be placed to make bite-sized activities for different groups.

The second lesson to consider from van Gogh’s art is process oriented. He was a disciplined “realist” as a sketcher and drawer when preaching in Borinage. Rather than asking what feelings or insights his subject evoked, he set out to produce near-photographic replicas of it so that its lines and shades were practically in his hand as he made them. Only after that step did he take the next one of discerning what he was seeing in and beyond what was there. All details are almost necessarily included in these first stages, so that they can be artfully omitted in the final ones.

The great writer Kurt Vonnegut (who hails from Indiana, I’m required to quickly add) makes a similar point in his novel Bluebeard. The book is the fictionalized autobiography of Rabo Karabekian, an abstract-expressionist painter. His art is experimental and wholly “unrealistic.” But his training was much more conventional. In fact, as a youth apprentice he was assigned the task of drawing and painting a perfect replica of a ruble note, one that would be so convincingly real that it could be passed even under the suspicious eyes of vendors in the local market. His later work forgets such detailed realism, but requires the skills and disciplines of that apprenticeship.

Van Gogh’s life ended even more tragically than did his ministry. But the world is still in his debt for the vision he brought to simple things, and the vision of the world his art can elicit in his grateful admirers.